A Copyright Takedown and the Changing Life of Protest Music

The removal of Zohran Mamdani’s campaign video reveals how copyright rules can affect political messages, which is sparking conversations and raising new questions. Courtesy of badosa via Flickr

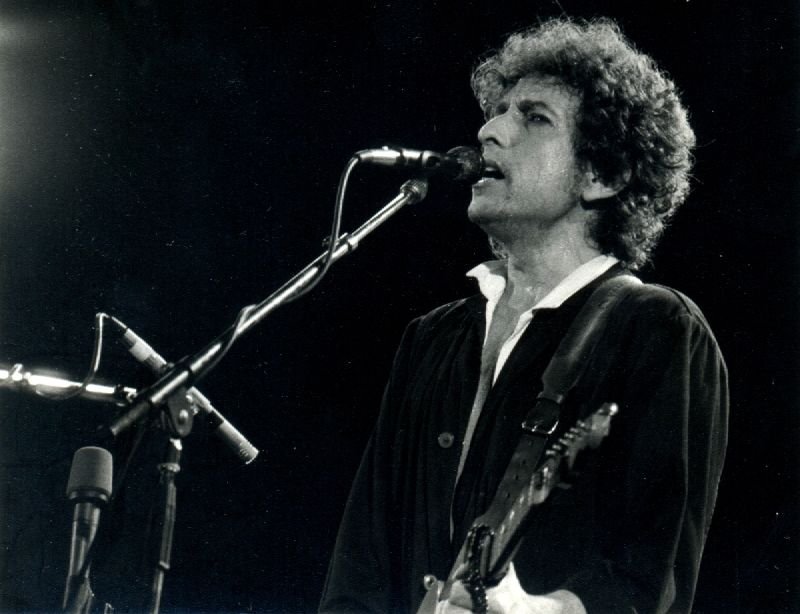

When New York mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani released a 2025 campaign video set to Bob Dylan’s “The Times They Are A-Changin,” the choice connected a modern political campaign to one of the most recognized protest songs of the 1960s. Within hours of its release on X, the video was removed following a copyright takedown initiated after Dylan’s publisher declined to license the song for political use.

Universal Music Publishing Group maintains a standing policy “not to license Dylan’s music for projects involving political figures,” a spokesperson for UMPG said in a statement, according to the New York Times. Once the campaign’s video was posted, automated copyright detection systems on digital platforms triggered its removal.

The incident immediately drew attention because of the song involved. Written in 1963, “The Times They Are A-Changin’” has been associated for decades with social-justice movements, youth activism and civil-rights demonstrations. The takedown introduced an example of how a politically significant song from one era interacts with the legal and commercial frameworks of another.

Historically, protest songs traveled freely. They circulated through marches, rallies, community gatherings and radio or television broadcasts that did not require political campaigns to secure special licensing. A song could become the soundtrack of a movement simply because people sang it together, or because broadcasters chose to air it.

During the 1960s and 1970s, organizers relied heavily on live performance and noncommercial spread. Many groups adopted existing songs without needing formal permission, because their political communication rarely involved recorded audiovisual content.

Today, however, the landscape is very different. Political messaging now relies heavily on digital videos posted on platforms like YouTube, Instagram and TikTok. These formats fall under synchronization licensing rules, which require campaigns to obtain explicit permission from both the song’s publisher (who controls the composition) and the owner of the sound recording (usually a record label). Without approval from both, a song can be blocked, muted or taken down entirely.

These rules apply no matter how iconic or politically meaningful a song may be. Even music deeply tied to historic movements such as civil rights or women’s suffrage is treated the same as any commercial pop track in the eyes of copyright law.

Publishers and rights holders maintain complete legal authority to approve or deny political uses, and in recent years, many companies have adopted broad policies refusing all political licensing requests. This is partly to avoid appearing partisan, but it also reflects the increasingly cautious approach of major media companies.

The result is a new reality: while protest songs once belonged to the public as tools of political expression, their modern use in digital campaigning is now controlled by legal and commercial systems.

Dylan’s catalog, acquired by UMPG in 2020, falls under these protections. As a result, a candidate’s decision to reference a historically political work becomes dependent on compliance with the rights holder’s policies, even when the song’s original meaning was connected to public activism.

The removal of Mamdani’s video shows how copyright rules can affect political messages that use important protest music from the past. It also reveals how access to cultural material from earlier activist movements is now controlled by today’s legal and commercial systems.

As political campaigns work within these rules, the incident raises key questions: How does copyright law shape the political use of meaningful music? How do old protest songs fit into digital media today? And how do different generations connect with the musical traditions of past movements?

As political campaigns keep using digital video, these copyright issues play a big role in how today’s candidates connect with the culture of earlier generations. The Mamdani–Dylan example shows how protest music from the past meets today’s legal system, and it raises important questions about how future campaigns will handle the same challenges.